History of Floorcloths

PAINTED FLOORCLOTHS:

An Historical Perspective

By Jeanne Gearin

Floorcloths are part of our American heritage. They are also called floor cloth carpets, painted canvas, oil cloths (oyle cloths), floor canvases, checquered canvas, grease cloths, crumbcloths (crumcloths) or druggets. The word “floorcloth” is often printed as one word, two words or hyphenated.

At least three of our presidents had floorcloths. George Washington purchased them for Mt. Vernon. When John Adams left the White House, there was a floorcloth listed in the inventory. Thomas Jefferson had at least two floorcloths in the Presidential Mansion — one in the small dining room “to secure a very handsome floor from grease and the scouring which that necessitates” and one in the great hall. These floorcloths were probably painted plain green according to the inventory. Jefferson also had painted canvases at Monticello.

Floorcloths were rather expensive. George Washington’s purchase of one in January 1796 cost $14.28. Because Thomas Jefferson considered the English floorcloths to be of better quality, he reluctantly paid about $3 a square yard for the above mentioned cloths. A 1746 inventory valued a painted floorcloth at 10 pounds and in 1827 Samuel Perkins and Son of Boston, Massachusetts, advertised “for sale a large and elegant assortment of painted floorcloths, without seams, some in imitation of Brussels carpet,” from $1.37 1/2 to $2.25 per square yard.

Advertisements indicate that floorcloths were widely used. Discounts of 10% were offered to merchants and builders purchasing in quantity. Advertisements in the 18th century also offer custom shapes, sizes, decor and colors.

William Burnet was governor of New York, New Jersey and then of Massachusetts. The inventory at his death in 1729 reported “two old checquered canvases to lay under a table: and a “large painted canvas square as the room.” In the South, the posthumous inventory of the effects of Robert “King” Carter, listed “one large oyle cloth to lay under a Table” and “one large floor oyle in the “Dining Room Clossett”. Robert Carter was called “King” because of his extensive land holdings in Virginia. Peter Faneuil, the wealthy Boston merchant, also owned floorcloths. Because they were so valued they were included in estate inventories and were also painted in the backgrounds of portraits done in the 18th century. Public auctions of household goods also often listed floorcloths.

Originally floorcloths were imported from England. The Factory of Smith and Baber of South Kensington, London, produced painted floor canvases prior to 1754. Nathan Smith, the founder of the above firm, first produced block printed cloths in 1754. His early cloths most likely consisted of only one color, but by the 19th century as many as five colors were not unusual. Historians believe they were adapted from the 14th century French wall and table coverings which were made in a similar manner.

Early cloths were produced by a method of stenciling similar to wall stenciling. As their popularity increased coach, sign, house painters and itinerant artists were designing and selling floorcloths. An advertisement in the Maryland Gazette of June 26, 1760, refers to a runaway indentured servant who could “paint Floor cloths as neat as any imported from Britain.” Apprentices to ornamental painters were often family members. In Boston, John Johnson and Daniel Rea, Jr. advertised until 1789 that they did floorcloths “in cubes, yellow and black diamonds, and turkey Fatchion.” Thomas Johnson, John’s father and Daniel’s father-in-law, was a well known ornamental painter working in Boston in the first half of the 18th century. According to their account books, they painted one-color cloths and fancy cloths with borders and even one “cloath with a Poosey-Cat and a Leetel Spannil.”

When home artists took up the practice of making floorcloths, some did so without adequate knowledge of the process and produced disasters. From various early accounts we find that craftsmen often ran into chemistry problems similar to those we experience today. Compatibility of materials, inadequate drying times, and improper bonding of paints regularly caused cracking. Even the imported English floorcloths, which were considered better than domestic ones, often arrived damaged due to shipping mishaps or inadequate drying.

In 1807 John Dorsey of Philadelphia had two looms on which he made carpets and floorcloths. He referred to his products as “floor coverings” and they were similar to those made in England. Other manufacturers and importers of floorcloths or oil cloths were listed in American directories in the 18th and 19th centuries, but little is known about their methods or production. However, in 1811 J. Harmer advertised in the New York Directory that his cloths were “wove in the same manner and of the same quality as it is at English Factories.” In 1817, New York Pattern Floor-cloth Manufactory, 35 Rivington Street, advertised in The New York Annual Advertiser “the greatest variety of the most approved patterns…of any size or form and less liable to crack than Floor-cloths imported from England”. They also advertised “Old Floor-Cloths re-ornamented in the best manner, on reasonable terms.” The illustration on this advertisement shows a large roll with a Greek key border and a small overall starred pattern, probably an imitation of a “Turkey carpet.” Terms are given for one, two, three, four or more colors.

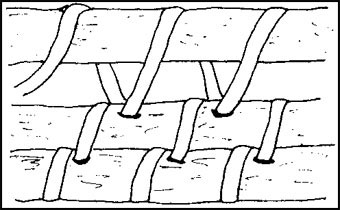

The following historical method of making canvases was contained in The Illustrated Exhibitor and Art Magazine, published in 1852. The material used was made in Dundee, Scotland, of flax and hemp. They were woven on large looms which were constructed to accommodate the rolls which ran approximately 113 yards by 8 yards. This length (longer than a football field), was necessary to keep them from having to be seamed. Narrower widths for stairways and halls were cut from these rolls. After being folded into 3 foot square bales, weighing about 500 pounds, they were shipped to London.

The canvas was then stretched on large frames. These frames were in a room with 30 foot ceilings and over 90 feet in length called a “straining room.” Scaffolds were erected between the frames with just enough room for a man to stand and paint first the front of one canvas and turn around and paint the back of another. The canvas was first sized and sanded with pumice to a smooth surface. Extra heavy paint was troweled on, allowed to dry, pumiced again and built up to three coats. Drying time took two to three months. No dryers were used as they would cause the paint to crack. This large, cumbersome, heavily painted canvas was then rolled onto wooden rollers to prevent damage. It was then pulled into the printing room to be decorated. The rollers were fitted into iron sockets similar to a roller shade and gradually rolled out on the tables to be decorated.

An article in The Golden Cabinet in 1793 in Philadelphia describes a process similar to the English method. However, the addition of white lead to the paint was recommended to enhance drying.

The earliest cloth decorations imitated fine wood, marble, tile and fashionable Turkey carpets. They were also “tessellated.” In the 18th century geometrics were both plain and marbled. They were stenciled, painted freehand, and block printed. For authentic patterns refer to “Various Kinds of Floor Decorations Represented in Both Plano and Perspective,” the 1739 publication by John Carwitham of London.

Colors used were chromes, Prussian blue, azure blue, black, vermilion, malachite green and others. Yellow ochre was the most popular background color. The paints were mixed with linseed oil. Oil cloths received their name from the heavy amounts of linseed oil used in the paint.

In the 19th century quilt patterns became popular. As styles changed the English designer, Charles Eastlake, recommended simple geometric patterns in two colors or shades and definitely not imitations of marble or anything else which could be considered grandiose. His book printed in England and reprinted in 1872 in the United States, signaled a return to simplicity.

Floorcloths were used in summer when wool carpets were removed and as protective material under tables or in hallways. They were used also as insulation under carpets during cold weather. They waned in popularity in the 1850’s, and were relegated to the kitchen or hallways and were last referred to as oil cloths in the 1870’s.

Linoleum (originally a trademark) was invented in England in 1863 and subsequently manufactured in the United States. It became the floor covering of choice. An advertisement from a Sears Roebuck catalog recommends it as being “like oil cloth, but heavier, more durable and softer to walk on.”

In the middle of the 20th century, with the renewed interest of decorators in historic restoration, floorcloths became popular again. Articles have appeared in many home decoration and antique magazines concerning their history and traditional construction as well as modern methods of making them employing silk screens and water-based paints.

In a letter from “E.W.” (Edward Winslow) to a friend in England, he says: “And God be praised, we had a good increase…. Our harvest being gotten in, our governor sent four men on fowling that so we might after a special manner rejoice together….” Winslow continues, “These things I thought good to let you understand… that you might on our behalf give God thanks who hath dealt so favourably with us.”

In a letter from “E.W.” (Edward Winslow) to a friend in England, he says: “And God be praised, we had a good increase…. Our harvest being gotten in, our governor sent four men on fowling that so we might after a special manner rejoice together….” Winslow continues, “These things I thought good to let you understand… that you might on our behalf give God thanks who hath dealt so favourably with us.”

The National Museum of the American Coverlet focuses on antique American woven coverlets. Dated coverlets in the collection range from 1771 to 1889.

The National Museum of the American Coverlet focuses on antique American woven coverlets. Dated coverlets in the collection range from 1771 to 1889.