Colonial Gardening

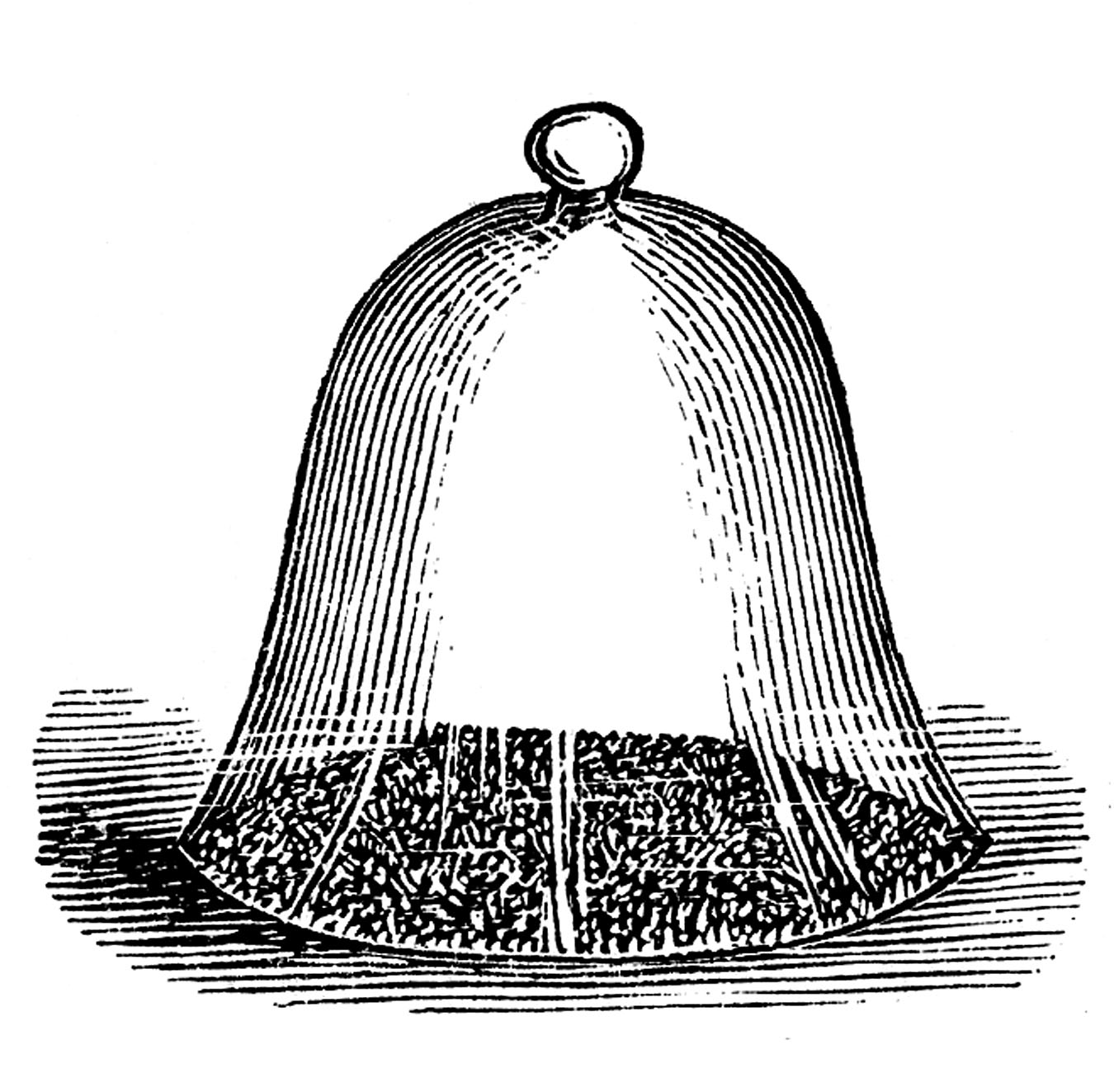

Colonial gardens of 17th and 18th century America were as varied as the gardeners themselves and the locations in which they lived. While some gardens followed no plan, others were intricately laid out. Some gardens had plants designated to specific areas, while others were planted in a seemingly haphazard manner mixing tall plants with short ones, flowers with vegetables, and herbs mixed in amongst them all. Garden beds, varying in size and shape according to what was grown in them, were often raised by building up the soil and placing tree saplings on the ground around them. The purpose of raising the beds was to improve drainage, which garnered much attention. Walkways were usually made of tamped soil, gravel, clamshells, or brick, and were just wide enough for one person to walk through and weed the beds. The main walkways were, however, wider because they led to an outbuilding, namely the privy, located at the farthest end of the garden.

Dutch gardens in New York, as well as those of merchants and townsmen of Virginia, were laid out in symmetrical patterns, yet were simple, functional, and well-balanced. Natural landscaping was seen as something that needed to be tamed and trimmed, not recreated, and resulted in gardens that resembled those of their homelands. Gardens were located near the kitchen house with walkways leading to many of the other outbuildings. The walkways were laid out geometrically in patterns such as basket weave, running bond, and herringbone and designed with either right angles or acute angles. Planting beds were “raised up” by boards allowing for good drainage, ease in planting, tending, and weeding.

Fences were required by law as early as 1631. Legislation in 1646 set the minimum height of the fence at four and one-half feet and “close down to the bottom”. In 1705, the General Assembly enacted legislation to protect gardens from stray horses, mares, cattle, hogs, sheep, and goats. The fence had to be sturdy enough and so close that “none of the creatures aforesaid can creep through”. Post and rail fences, as well as picket fences, were typical for private gardens. The outlying borders of the fields were generally enclosed with a “worm” or “snake” fence, later known as the “Virginia rail”.

Early colonists acquired seeds and plants by bringing them from their homelands, or through extensive exchanges across the Atlantic with friends and family. As a result, the majority of fruit trees, vegetables, herbs, and flowering bulbs came from Europe. Some plants such as the tomato and potato, although native to the Americas, came back to the colonies via these exchanges. These plants offered a sense of familiarity in an otherwise unfamiliar territory. Vegetables grown in the kitchen garden would have included leeks, onions, garlic, melons, English gourds, radishes, cabbages, and artichokes. Other vegetables that were needed in larger quantities like corn, beans, and pumpkins, were grown in the larger, outlying fields. Many vegetables and herbs served culinary, as well as, medicinal purposes while flowers were not only edible, but served as dyes and perfumes.

In summary, colonial gardens of the Dutch, merchants, and townsmen were simple, functional, symmetrical, and well-balanced in design while others were simply functional. Common features include raised beds, walkways, and an enclosure in the form of a “nature fence” or a wood fence to keep out stray livestock. Placement of these gardens was generally near the kitchen where they grew an assortment of vegetables, herbs, and flowers.

Taken from Colonial Gardening by Deb Browning

In a letter from “E.W.” (Edward Winslow) to a friend in England, he says: “And God be praised, we had a good increase…. Our harvest being gotten in, our governor sent four men on fowling that so we might after a special manner rejoice together….” Winslow continues, “These things I thought good to let you understand… that you might on our behalf give God thanks who hath dealt so favourably with us.”

In a letter from “E.W.” (Edward Winslow) to a friend in England, he says: “And God be praised, we had a good increase…. Our harvest being gotten in, our governor sent four men on fowling that so we might after a special manner rejoice together….” Winslow continues, “These things I thought good to let you understand… that you might on our behalf give God thanks who hath dealt so favourably with us.”